September 07, 2013--Operation WOOHOO

15:13

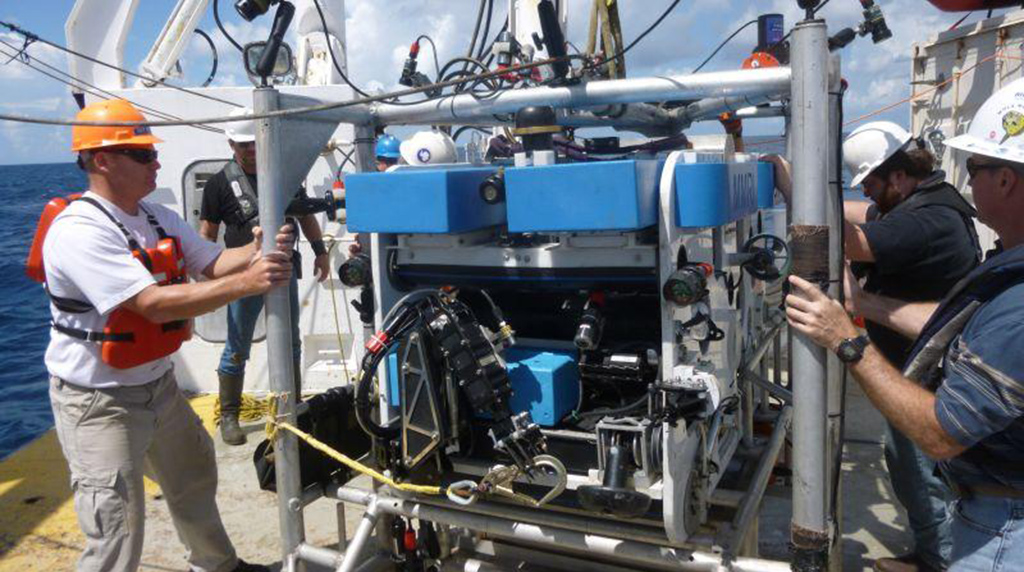

Once on deck, the team immediately began to tackle the issues. One of the first problems is that the port thruster on the SSD quit working. We don’t know why this happened, but luckily Matt has extras.

19:31

We still haven’t put the SSD in the water. When we retrieved the SSD earlier today, communication ceased. The problem was the main fuse was blown and it is going to take a while before the team can replace it. However, a new development occurred: two of the three main thrusters on the SSD are bad and needed to be replaced.

01:17

The SSD and I-Spider package are ready to be lowered to retrieve Mola Mola. This is the last shot. The team configured the SSD to operating with 3 thrusters rather than 5, and the recovery package has been modified so as to not become entangled in the SSD.

02:00

The SSD and I-Spider are being lowered.

The plan was that Matt and Steven would operate the SSD, with Steven driving the vehicle and Matt operating the arms. Prior to deployment, the team placed a bag containing a line thad a snap hook attached to each end. The snap hooks were placed in the SSD’s hands so that when the vehicle was close enough, Matt could extend the arms and snap the hook to Mola Mola’s recovery hook. The other end of the line would snap onto the SSD frame, then the SSD would lock back into the cage and we would pull the entire package up using the A-Frame winch. That was the plan. It was an excellent plan! We landed within 3 meters of Mola Mola and exited the cage at 02:22. You could not have asked for a better position. Mola Mola was directly in front of us. Everyone was in the wetlab turned command center watching closely on the HD television monitors as Steven carefully approached Mola Mola with the vehicle. The eye on top of Mola Mola that is used for launch and recovery is the target for the snap hook. Steven approached the broad side of the vehicle and Matt extended the arms. After a couple of passes, SNAP! WE GOT IT! It was just as the team planned. Steven parked the SSD back into the cage, Matt secured the other snap hook onto the cage, and slowly began the recovery ascent. Everything went exactly as planned. We hauled Mola Mola up on the back deck at 02:56. It was a team effort. Everyone aboard this vessel worked their part in one way or another, from deck operations and locating Mola Mola, to Tad keeping the vessel steady as they lowered a cable 1,230 meters with a 1,500 pound ROV package to within 3 meters of a target in 3-5 foot seas (that’s excellent driving folks), troubleshooting problems as they arose, to keeping everyone well fed and humored. What an incredible experience and what a great way to showcase teamwork and collaboration. SUPERB!!!

September 06, 2013--Operation Recovery: Mola Mola (Day 2)

12:58 CST

We deployed SSD/I-Spider at 12:10 p.m. and the team is confident that we will have a successful mission. The recovery line was recoiled and placed back into the bag, so as not to come out too early. Deployment was smooth. The seas are much better today. Currently, the team is tracking Mola Mola using sonar and we are 37 m to the north, northeast from it. The SSD/I-spider is on the seafloor. The current depth is 1,226 m. Confidence is high.

13:01 CST

We have a visual on Mola Mola. Now, we are setting the SSD/I-Spider on the seafloor and are preparing to deploy the SSD to attach the recovery line and retrieve Mola Mola. We are 8.6 meters from Mola Mola, which is pretty good considering we lowered the SSD/I-Spider 1,230 meters in 1 meter seas. The Pelican is pitching quite a bit, but everything looks good on the bottom.

14:22 CST

We’re tangled, again. The cage was too far from Mola Mola, and that made the capture line too short for attachment. The problem was that once all of the line was pulled out, we thought we could pull the cage a bit closer. With all of the line out, along with the ship’s pitching, we simply got too tangled. We loaded it back in the cage and hauled on deck. The team is now considering attaching the tool bag containing the recovery line to the SSD, rather than to the cage. We should be back in the water within an hour.

GUEST BLOGGER

Name: Max Woolsey

Title: Undersea Vehicles Engineer

Institution: NIUST

Project/Affiliation w/ECOGIG (Research Scientists): My primary involvement with ECOGIG is operating, maintaining, and modifying the AUVs Eagle Ray and Mola Mola. Additionally, I provide engineering support in the placing and servicing of the ECOGIG seafloor landers and the turn-around of the moorings that are continuously sampling in the Gulf.

Plan of study (Students):

How many research cruises have you been on? Right around 25 cruises, with the early ones mainly focused on seismic work.

What is most enjoyable about this research cruise? The weather has been unusually calm. This makes the vehicle launches and recoveries a breeze. Also, we've had great teamwork between the AUV crew and the enthusiastic students.

What do you like most about your work? I enjoy the continuous engineering challenges presented by the vehicles and their scientific goals.

What are the most challenging aspects of conducting research in an oceanic environment? Operations often continue around the clock, which can be somewhat stressful. Weekends and holidays mean little during the course of a cruise. Because of the extreme conditions at depth and complexity of the vehicles, components must frequently be repaired and replaced, and software must frequently be tuned and modified. In the dynamic conditions at sea, this work can be difficult.

How does marine technology help with oceanographic research? The technology we have available determines the way we conduct our research. With the AUVs, we are able to map the seafloor and subbottom structure with a resolution far greater than could be attained by ship operations alone.

Where do you think the future oceanographic research is headed? Specifically in the area of undersea vehicles we are seeing great improvements in batteries, navigation systems, and sensors. With the increased battery capacity comes fewer launch and recovery cycles due to the longer available mission time. New and improved chemical sensors and sonar systems will allow greater measurement capability, and with higher resolution sensors, the need for greater navigational accuracy grows. Autonomous systems will eventually be used more autonomously, but for now, operator presence provides greater oversight and the capability for assessing and correcting vehicle navigation.

September 05, 2013--Operation: Recover Mola Mola

The seas have been a bit rough and some of us, including myself, are a bit nauseous. We monitored Mola Mola’s movement and position for nearly 40 hours prior going into port to pick up the SSD/I-Spider. We arrived on site around 5:30 p.m., woke up Mola Mola and it is right where we left it! The team was very relieved. It's windy and the seas are about 2-4 feet and seem to be building. Battling changing weather conditions and dealing with seasickness is one of the greatest challenges of living and working 24/7 on the ocean. Prior to deployment, Matt and the rest of team had to connect all of the attachments (USBL transponder, cameras, lights, and cables), which were removed during shipment. This all went without a hitch and we were ready to start the deployment at about 23:00. A recovery line with a snap hook was packed into a tool bag that was strapped to the cage. The idea was than it pull out as the SSD exited the cage and swam to Mola Mola. However, while on its descent, the line extricated itself from the bag prior to reaching the seafloor. This casued the excess line to become entagled in one of the SSD's thrusters and we doubted whether or not we would be able to contiune with operations. We located Mola Mola after making several passes, and using sonar we tried to get within 30 meters of it. After an hour of sonar tracking, we finally caught sight of Mola Mola with one of the 8 cameras on I-Spider. We immediately set the SSD/I-Spider down on the seafloor and tried to exit the cage. The depth was 1,226 meters and Mola Mola was sitting upright and appeared to be in good condition. There is no current at this depth, which allowed Mola Mola to remain motionless. Moreover, the sediments at this location and depth consist of fine-grained silt, and any disturbance of the seafloor easily can suspend the sediments, thereby reducing visibility for quite a long time. Using the SSD thrusters, Steven tried to blow away the suspended sediment, but to avail. We had to wait about twenty minutes. After visibilty was reestablished, we tried to exit the cage, but were unable to due to the entangled recovery line in the SSD thruster. We abandoned operations and locked the SSD into the cage and recovered the package. Poor Mola Mola was left alone on the seafloor. Recovery of the package was quick and smooth. The systems are no on charge, as they both operate off battery power, and the team is thinking of ways to redesign the recovery system. We will try again in the morning. The weather forecast looks good. I will post later this morning when recovery operations begin.

GUEST BLOGGER

Name: Roy Jarnagin

Title: Undersea Vehicle Systems Engineer

Institution: National Institute for Undersea Science and Technology (NIUST) / University of Southern Mississippi

How many research cruises have you been on? Ten or so. I haven’t actually kept count.

What is most enjoyable about this research cruise? The weather has been perfect and the AUV launch and recovery operations have gone extremely well. (That is usually the most difficult part of the operation.)

What do you like most about your work? Autonomous Undersea Vehicles (AUVs) are amazing wonders of technology. The experience of working with these machines never gets old.

What are the most challenging aspects of conducting research in an oceanic environment? From the AUV perspective, the intense pressure of the deep ocean along with the severe consequences of seawater entering delicate systems is the ever present challenge. From the human operator perspective, launching and recovering in anything other than ideal conditions is a huge challenge. The AUVs are graceful in the water, but are too much like very, very expensive wrecking balls when hanging from a ship’s crane in seas.

How does marine technology help with oceanographic research? Ocean scientists need data to do their work of discovering how the earth’s oceans and related systems function. The high resolution seafloor map products that are produced from the data our AUVs collect are important to understanding ocean processes.

Where do you think the future oceanographic research is headed? This may be a surprising view coming from an engineer working with robotic systems, but I think the future of discovery in ocean research is mostly dependent on gifted people willing to devote their lives to that cause. The technology will certainly advance, but technology cannot replace the human creativity, ingenuity, curiosity and tenacity that lead to discovery and advancing human knowledge.

Other notes: Working at sea with deep ocean technologies is an amazing adventure. The work involves hard physical work and stressful situations, but offers a tremendous sense of accomplishment when operations succeed. I feel that I am truly blessed to be involved in this work.

GUEST BLOGGER

Name: Marco D'Emidio

Title: Research Associate

Institution: MMRI-NIUST University of Mississippi

Project/Affiliation w/ECOGIG (Research Scientists): Auv Mapping- Lander operations

How many research cruises have you been on? A lot. At least let’s say 30 ish in the past 3 and a half years.

What is most enjoyable about this research cruise? I am the data manipulator, so of course when Max comes with the hard drive full of raw data of multibeam, subbottom profiles and navigation logs, I take care of that. Also I like the deck ops, just to make sure the auvs are safe!

What do you like most about your work? Well, as I already said, when you create maps and images from a bunch of raw files full of weird numbers, that's a real satisfaction. Also because I show the other guys that their hard work has paid off.

What are the most challenging aspects of conducting research in an oceanic environment? Well, as you are experiencing, the most challenging aspect is trying to contain yourself from eating everything eatable all the time, constantly. Said that, I think working at sea is challenging by definition. When you are at sea you are in 24/7 alert mode. Anything could happen at any time, and dealing well with this condition it's the most challenging aspect. Then if you are good at your job everything will come along.

How does marine technology help with oceanographic research? Marine technology helps to reach what you have been dreaming about some years ago.

Where do you think the future oceanographic research is headed? Oceanographic research is the future

September 04, 2013--Preparing for the Rescue Mission

We arrived back at the LUMCON port in Cocodrie around 7:00 a.m. By the way, “Cocodrie” comes from the Spanish word “cocodrilo” meaning crocodile. The crane was not going to arrive at LUMCON until 10:00 to unload the Eagle Ray trailer and LARS, so we had a couple of hours of down time. I spent the morning catching up on some reading then rode with Marco, Alex, Clayton, and Ryan to get some boat supplies and check out Cocodrie and Chauvin. These are very picturesque towns built right in the middle of the marsh. Bayou Petite Coullie runs along the highway and is just wide enough for a couple of shrimp boats to pass through. It is choked with water hyacinth and duck weed in many parts, but is very beautiful, nonetheless. The crane finally arrived around two o’clock to offload the AUV. It took less than 30 minutes to offload everything. The crew is very efficient and I’m sure they wanted to have a little down time as well! Dinner was incredible tonight! Chef Alex grilled some fresh red snapper and oysters on the half shell. Pass the hot sauce please! I think everyone really enjoyed it. Matt and Steven called around 6:00 p.m. and said that they were just leaving Oxford with the Station Service Device (SSD) and the i-Spider. It’s at least a seven hour trip from there, so I spent the rest of the evening exploring the salt marsh around LUMCON. Salt marshes are very dynamic environments and the plants and animals that live there must be adapted to extreme conditions. Spartina alterniflora (cordgrass) nd Juncus roemerianus (black needle rush) are the dominant “grasses” in the marsh. These not only provide habitat for a number of fish, invertebrates, like stone crabs, hermit crabs, and marsh periwinkles, birds, such as the clapper rail and gallinule, egrets, and herons, they also prevent erosion and help stabilize the marsh. They also help reduce pollution and toxins, remove excess nutrients from runoff, and act as a buffer to prevent against tropical storms and hurricanes, which is perhaps the most important ecosystem service that the marsh provides to the people who live here. More importantly, this land is being lost to the sea from subsidence mainly as well as sea level rise and reduced sediment nourishment. It is truly a magical place and protecting and restoring our wetlands is an issue that I am very passionate about.

It is very late and Matt and Steven just arrived with the SSD and i-Spider, and it is really cool! I can’t wait to see this thing in action. By the way, these things were built from scratch by the team that is aboard this vessel! I feel pretty honored to work with these folks. We are now steaming 100 miles due south of Cocodrie to GC600, the site where we lost the AUV. Marco and I just finished securing a 72-inch HD television in the wet lab, which is now a dry lab since we are not filtering seawater. Max is configuring the top-side box for the SSD and the i-Spider. The i-Spider will be sending us a live camera feed as it descends to over 1200 meters. I wonder what we will see? Squid? A whale? Trichodesmium (I’m sure of this). What kind of fish? I hope we see a Mola Mola, that’s for sure! I will update later today. Until then...

GUEST BLOGGER

Name: John Ahern

Title: Tech Manage

Institution: LUMCON R/V Pelican

Project/Affiliation w/ECOGIG (Research Scientists):

How many research cruises have you been on? I've been on a lot of cruises. I worked as a tech on the R/V Cape Hatteras for 4 years, the pelican for the last 2 and I also did some work on the E/V Nautilus as an ROV Pilot.

What is most enjoyable about this research cruise? The weather has been great and the scientists are good natured which always makes cruises fun.

What do you like most about your work? I like getting all of our systems up and running as they should be and serving scientists needs to a high standard.

What are the most challenging aspects of conducting research in an oceanic environment? The toughest thing is the unpredictables. We make a great effort to prepare for any issue we might have at sea and design in as much redundancy as we can. but unexpected failures sometimes and those are tough. and bad weather always makes everything more difficult.

How does marine technology help with oceanographic research? I think if it wasn't for technology we would only have what we can see and when it comes to the ocean, that's not much. So, technology is critical and it’s still developing. There is great potential to create even more comprehensive pictures about what is going on in the ocean with technology. For example one ctd cast gives you a tiny slice of data but if you could know all the parameters all the time for the entire world’s oceans, that would be something. In some ways this is already done with ARGO, but can be expanded.

Where do you think the future oceanographic research is headed? I think that satellite remote sensing is part of where research is headed, to know everything all the time and then to move on to what that means for all different aspects of oceanography from biology to currents, weather influence, heat flux, etc. and use the data for modeling.

September 03, 2013--Research in a Challenging Environment

Eagle Ray completed its second mission earlier today at GC647 and is now on the back deck. The mission went very well and the team is pleased with all of the data Eagle Ray collected. However, an unexpected situation developed that has the team very concerned. We deployed Mola Mola on Sunday night under excellent conditions. She descended to the bottom (1,224 meters), dropped the large descent weight and began working on the survey that we had programmed her to execute. After less than an hour, she suddenly stopped moving and ceased all communications. Ordinarily, if a simple failure of the computer or power system were occur, she would drift slowly to the surface. The fact that she did not tells us that she is heavier than normal and that might mean that one or more of her housings has flooded. We waited for 24 hours to allow time for her emergency drop weight (released by a corrodible link) to activate but did not see any movement; we are able to track her precisely using an independent USBL beacon that is configured to operate under specifically these conditions.

Vernon called Matt at the shore side support at MMRI (Mississippi Mineral Resource Institute) and asked for his advice. He immediately offered to bring the SSD Remotely Operated Vehicle and the I-spider out here to attempt a rescue. The current plan is for us to return to Cocodrie tomorrow, offload Eagle Ray, onload Matt and gear, return to this location and begin the rescue attempt, perhaps as early as Thursday evening. I have no doubt that we will be successful. While losing Mola Mola was unsettling, this team embraces challenges and has shifted the mission focus to recovery. Moreover, the success of the mission also will be in demonstrating the capabilities of the SSD and I-spider. Besides, these are really cool machines and it would be a shame to not get to see them in action.

In algal news, Tracy collected more Trichodesmium. His experiments are running smooth and he has lots of Trichodesmium data to work with. While sampling this morning he observed a surface slick that was more than 5 miles long by the bridge's reckoning. He said this slick was not visible from the deck, but quite visible from the O1 deck (upper deck). I also observed oil this afternoon, but they were mere blobs. We have Eagle Ray loaded into the trailer and the team is getting everything ready to offload at Cocodrie in the morning. Once we have the SSD, the I-spider, and Matt, we will immediately head back to the site where we lost Mola Mola. I will post tomorrow evening once we are underway. Cheers!

ECOGIG TEAM PROFILE

Name: Vernon Asper

Title: Professor of Marine Science

Institution: The University of Southern Mississippi

Project/Affiliation w/ECOGIG (Research Scientists): Scientist

How many research cruises have you been on? ~75 totaling about 1400 days at sea

What is most enjoyable about this research cruise? Working with students and with technology

What do you like most about your work? Working with students and technology

What are the most challenging aspects of conducting research in an oceanic environment? Working with students and technology!!

How does marine technology help with oceanographic research? It’s what I do. We are able to make measurements that were impossible only a few decades ago. We are also able to communicate far better while at sea so that we can transfer data, seek help from experts, and make logistic arrangements from the ship.

Where do you think the future oceanographic research is headed? More AUVs and gliders

Other notes: The Macondo oil spill has changed our lives and defined our careers because of the unprecedented opportunity it represents to learn more about America’s Sea, the Gulf of Mexico

ECOGIG TEAM PROFILE

Name: Tracy Villareal

Title: Professor

Institution: The University of Texas at Austin

Project/Affiliation w/ECOGIG (Research Scientists): Phytoplankton

How many research cruises have you been on? 32

What is most enjoyable about this research cruise? I have lots of space and lots of Trichodesmium

What do you like most about your work? Phytoplankton are cool.

What are the most challenging aspects of conducting research in an oceanic environment? Getting out on it.

How does marine technology help with oceanographic research? It defines almost everything we can learn about the ocean

September 02, 2013--Data, data everywhere and not a byte to eat

Happy Labor Day! Today, the science team took some time to catch up data processing and instrument calibrations. However, the engineers thought today would be the perfect day to construct an underwater light out of a plain ol’ flashlight (Note: Never leave a group of engineers alone with time on their hands). While Vernon was instructing the students on operating a CTD and using the SeaBird software, Roy and Max were busy disassembling flashlights and hunting for light bulbs. I can’t wait to see this!

It was a pretty slow day for the most part. The seas were calm, the sky was blue and there was a slight breeze. Tracy was busy collecting samples and crunching data. Marco processed bathymetric data most of the day, but took some time to make espresso for the team. Max and Roy worked on data processing and logistics with Vernon for launching Eagle Ray later this evening. Between assisting with analyzing data and learning everything I wanted to know about CTD's, I spent some time catching up on reading. Perhaps one of my favorite aspects of working at sea is the amount of time I have to read. Some days we are really busy, but I always find time to read a chapter or an article. However, it seems as if there is never enough time to read on shore. It reminds me of the Twilight Zone episode "Time Enough at Last" with Burrgess Meredith, only I have not broken my only pair of glasses! Well it's time for our pre-dive brief. We will launch Eagle Ray tonight at 10:00 p.m. and will work in two hour shifts: I have the 02:00-04:00 shift. There's a peaceful calm at that time of night. Besides, Marco will be making espresso, so I have no choice but to stay up until dawn! Until then, cheers!

-A

GUEST BLOGGER

Name: Michele Jordan

Institution: USM student

Plan of study (Students): Marine Science

How many research cruises have you been on? Two, including this one.

What is most enjoyable about this research cruise? Getting to play hands-on with instruments I’ve never used before. It’s also been wonderful to work with people who have such enthusiasm for what they do.

What do you like most about your work? They gave me a week off to have this experience. Oh, the work on the boat. The fact that I get to learn something new every time we deploy, recover, or discuss an instrument.

What are the most challenging aspects of conducting research in an oceanic environment? Seasickness. It’s barely moving, seas under 1 ft, and I still have to wear the ear patch and grit my teeth when the ship rocks. I have the utmost respect for the people who can go out in weather.

How does marine technology help with oceanographic research? Technology either makes life exciting or safer. We can digitally measure parameters that once required time consuming mechanical and chemical methods. And it is so exciting to reach places that were once only the domain of heavily funded institutions.

Where do you think the future oceanographic research is headed? I think we’re headed towards focusing on human impact. All aspects of oceanography are impacted, some more directly than others, and some on much larger scales than others, but we can’t escape the fact that we force change and that change needs to be understood.

September 01, 2013--Why Trichodesmium is important

Tracy Villareal is studying the effects of oil and dispersant on the colonial cyanobacterium (blue-green algae) Trichodesmium. This genus is an important nitrogen-fixer in the open waters of the Gulf of Mexico and is one of the few organisms that can convert N2 gas into biologically useful forms. In most oil spills, the oil is in the coastal zone and has little impact on oceanic communities. However, the Deepwater Horizon spill occurred in deep, oceanic waters at a site where Trichodesmium is commonly abundant. Hence, it now is a relevant question to ask in order to understand some of the impacts that the spill had on the phytoplankton. The experiments are short-term incubations with crude oil and dispersants. Longer term experiments are very difficult with Trichodesmium since it disassociates and dies within about 12 hours or so of being collected.

Over the next few days, Tracy will look at various concentrations of oil, dispersant, and oil+dispersant. This follows up on work started in July on the R.V. Endeavor. Oil is pretty nasty to work with and sticks to everything. The standard glassware and caps used in N2 fixation experiments appeared to react with the oil and dispersant, and created outrageous variability in the results. Back to the lab. Now, he is out with treated glassware and silicone stoppers. The first runs are very promising and have quite respectable error bars showing significant differences between treatments and controls. The devil lurks in replication, though, so stand by for tomorrow's results.

The assay being used is based on the production of ethylene from actylene by the enzyme nitrogenase. This is the same enzyme that converts N2 gas to ammonia, and the assay if both sensitive and quantitative. The major downside is that it also picks up all sorts of compounds in oil. The standard assay in just seawater takes < 2 minutes. When oil is added, the run take 8 minutes. Multiply that by 4 reps, 5 treatments and 3 time points per vial, and it is a 10-12 hour day to set up the experiment, run the samples, and then do the dishes.

Eagle Ray mapping operations continued throughout Saturday night with teams of two alternating every three hours on standing watch. Eagle Ray completed its transects at 12:00 p.m. and was recovered soon afterward. The recovery was flawless! It was time to deploy Mola Mola and process the high-resolution multibeam data. However, once Mola Mola was in the water, the electromagnet that holds the sinker weight was not working properly. So, we lifted it out of the water and put it back on the 01 Deck to find out what was causing the problem. Roy and Clayton pulled Mola Mola apart and discovered a little bit of corrosion on the electromagnet face plate. Roy spent over an hour sanding the rust off. Mola Mola is now ready for deployment.

A new feature to this daily blog will be to have a guest blogger discuss their observations about the cruise. I thought this will provide a much better view of the scientific operations and day-to-day life aboard a research cruise.

GUEST BLOGGER

Name: Clayton Hugh Dike

Title: Graduate Student

Institution: The University of Southern Mississippi

Project/Affiliation w/ECOGIG: I am researching settling velocity of marine snow in the Gulf of Mexico.

Plan of study (Students): M.S. Marine Science

How many research cruises have you been on? 2

What is most enjoyable about this research cruise? Football games

What do you like most about your work? I enjoy being out on the Gulf.

What are the most challenging aspects of conducting research in an oceanic environment? The most challenging aspect of conducting research in an oceanic environment for me is resisting the urge to fish.

How does marine technology help with oceanographic research? Autonomous underwater vehicles utilize different technologies simultaneously to run missions including power, propulsion, navigation, and survivability. The technology involved with AUVs allows the platforms to place scientific instruments such as multi-beam echo sounders (MBEs), chirp sonars and cameras so that they are able to collect data usable to researchers.

Where do you think the future oceanographic research is headed? I think China’s maritime industry is expected to grow to 20% of its gross domestic product by 2020. A large maritime industry could be supported by new oceanographic research in the western Pacific Ocean.

Other notes: We recovered Eagle Ray today after it completed most of a survey at GC600. Later, we plan to launch Mola Mola which is now having a problem with the release mechanism.

GUEST BLOGGER

Name: Ryan Dodd

Title: Undergraduate

Institution: The University of Southern Mississippi

Project/Affiliation w/ECOGIG (Research Scientists):

Plan of study (Students): Marine Science

How many research cruises have you been on? This is my first research cruise. I’ve done a couple day-long survey cruises but nothing quite as extravagant or timely as this cruise.

What is most enjoyable about this research cruise? So far the most enjoyable aspect of the cruise is the deployment of the AUVs. There is a lot of excitement when deployment is achieved successfully. Basically, any work on deck is a treat. The water is crystal clear and vast. It is pretty overwhelming to look around and see nothing but crystal blue water and the occasional oil rig. Also, the food is fantastic.

What do you like most about your work? Being an undergraduate student I don’t really have a particular job on the cruise. Because of this I get to experience a little bit of everything aboard the ship. However, the environment is definitely what I like most about the work I’m doing. Granted, the weather has been perfect so far (knock on wood).

What are the most challenging aspects of conducting research in an oceanic environment? For me the psychological aspect of working in an ocean environment has been the greatest obstacle. It is pretty intimidating when you realize you’re in water over a 1000m in depth and any chance of rescue will take a while.

How does marine technology help with oceanographic research? Marine technology allows us to explore areas of the oceans unreachable. We are currently exploring cold seeps using AUVs. This technology is allowing us to explore hostile environments from the safe confines of our vessel.

Where do you think the future oceanographic research is headed? Oceanographic technology is going to continue to advance because there is still so much unknown about Earth’s oceans. There is always going to be a demand for new information and there is plenty of that in our oceans.

August 31, 2013--Eagle Ray Launch

Eagle Ray launch operations began at 9:00 a.m., with Max, Roy, and Marco calibrating the AUV navigation system. It is extraordinary and tedious process, but one that is absolutely necessary for a successful mission. The AUV ops team works under a strict code of checklists, operational rituals, and espresso (provided and prepared by Marco). Upon completion of the calibration and checklists, the AUV support crew launched Eagle Ray. The AUV crew said that 5 hours from calibration to launch might be a new record! The next step was to perform a patch test to calibrate the multibeam echosounder (MBES), which is used for mapping the seafloor. Once the patch test was completed, the Eagle Ray began its descent to 1200 m depth where it will perform mapping operations over an area of 1800 m x 1500 m at a speed of 1.75 m/s (~3.6 knots) throughout the night.

The seas were calm underneath a partly cloudy sky. The color of the water is perhaps one of the most magnificent colors that I have ever seen. It is the color of a sapphire gem glistening in sunlight. Streaks of golden Sargassum float on the surface and provide a brilliant contrast to the blue ocean waters of the Gulf. Because we are so far from shore, there is very little influence from rivers or land, which can introduce a large amount of sediment and nutrients that reduce water clarity. Here, sunlight can penetrate down to over 150 m, whereas, light will become absent in only a few meters in turbid, coastal waters. This is a perfect environment for a particular type of cyanobacterium, Trichodesmium, which is one of the most common components of the phytoplankton biomass in tropical oceans. Because Trichodesmium can “fix” nitrogen, it serves also as one of the most important sources of nitrogen in the sub-tropical surface waters in the Gulf.

An interesting feature that we saw today was the bubbling up of hydrocarbons. Although we are in beautiful blue water that is over 1300 m deep, we are sitting atop an active hydrocarbon seep. These are natural geochemical features and are quite common in the northern Gulf of Mexico. The smell of hydrocarbons was also strong. There was an oily sheen in some areas and every now and then we would see an oil bubble rise to the surface.

August 30, 2013--Welcome Aboard!

Our current mission will be to conduct seafloor mapping operations at lease block GC600 in the Gulf of Mexico using the Eagle Ray and Mola Mola Autonomous Undersea Vehicles (AUVs). The project is led by Dr. Vernon Asper from the University of Southern Mississippi Department of Marine Science (USM). Dr. Apser is a geological oceanographer interested in gas hydrates and will be using the AUVs to survey the site. The AUVs are operated by a team of scientists and engineers from the University of Mississippi and USM. The team includes geophysicist Marco D’Emidio, and AUV engineers Roy Jarnagin and Max Woolsey. Clayton Dike, a USM graduate student studying under Dr. Asper, will be assisting in AUV deployment and recovery operations.

The Eagle Ray (ER) is a torpedo-shaped AUV that operates at 20 to 50 m off of the seafloor. During the survey, ER will collect high resolution multibeam and sub-bottom profile data to characterize the bathymetry. Mola Mola (MM) will be deployed to investigate interesting features highlighted during ER operations. MM is used for dense photo surveys at an altitude of 3 m over an area 60 m X 60 m. The combination of these two AUVs provides a unique tool to investigate seafloor morphology and sub bottom profiles, while providing high resolution imagery of features of interest.

Other research projects will be to study the toxic effects of oil and dispersant on Trichodesimum, an important N-fixing genera of phytoplankton. Dr. Tracy Villareal (University of Texas Marine Science Department) will be collecting surface seawater samples at selected stations in GC600. I will discuss the project in greater detail in a later blog. Stay tuned!

We arrived at LUMCON early this morning where the AUVs and equipment were packed in a trailer on a semi. We anticipated spending the morning loading our equipment aboard the R/V Pelican and steam to our study site. That was the plan, and things always go according to the plan in science, right? Well, the trailer housing the ER weighs 18,000 pounds. The crane used to lift equipment aboard the vessel was not capable, so we had to wait for another crane to arrive. That crane arrived at 4:30 p.m. and after loading the trailer onto the starboard side of the backdeck , we felt confident that all systems were go. We unloaded the very delicate, 2,000 pound ER from the trailer and conducted a systems check of the AUVs. We quickly discovered that the ER was not communicating with vessel. This posed a significant problem and provided a very valuable lesson: always check your instruments and equipment before leaving port! Because its electrical components could not be exposed to the muggy air at LUMCON, we had to reload it into the climate-controlled trailer to troubleshoot the problem. It was now after 6:00 p.m. and we needed to eat dinner. It was going to be a long night. It was hot and humid. Mosquitos were biting. We were exhausted from waking up at 4:00 a.m. to drive from Stennis to Cocodrie to catch a vessel that was not there. We were ready to get underway. However, it is the problems that arise while conducting research that makes science fun! In part, it’s what drives scientific research and primes the potential for discovery. After dinner, ER was loaded back into the container and taken apart. To our surprise, the problem was simple: the battery connector was disconnected. Max said that this may have occurred during ER’s transport to LUMCON. Success! After a couple of snaps and clicks, ER was ready to come back out on deck. It is now after 10:00 pm, and although we are tired, the team and crew are happy. The engines are running and the lights of LUMCON are quickly fading into the night.

back to top

back to top