April 26, 2017

After the Deepwater Horizon accident in 2010, scientists estimate that as much as 15% of the oil sank to the seafloor. Cold bottom water temperatures in the Gulf and low activity of organisms living in the sediment means the oil that made it there after the accident has degraded extremely slowly. The oil degradation that has happened is thanks to the work of microbial communities that live on and in the seafloor. Researchers know that microbes can break down natural and human supplied oil and gas in deep water systems, however it is not understood how these seafloor microbial communities respond to high loads of oil, such as the amount released during the Deepwater Horizon accident. Thanks to the presence of a high number of natural oil seeps in the Gulf of Mexico, it is thought that microorganisms in the Gulf are "primed" to begin oil degradation after a big event, but this has not been easy to determine for certain, as there are many technical challenges presented when working in the deep sea.

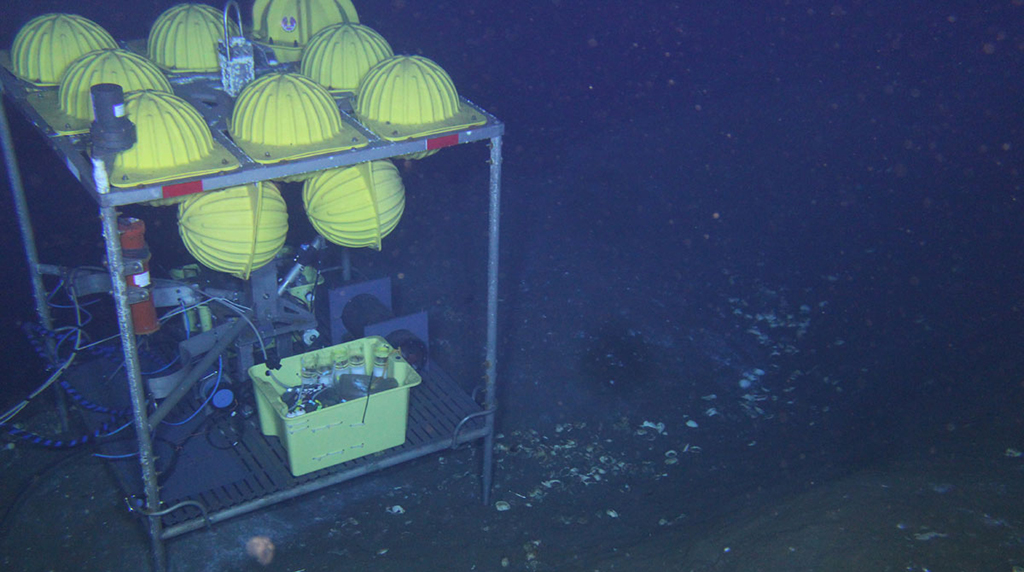

A recent paper published in Elementa by researchers, including ECOGIG team members Beth Orcutt, Laura Lapham and Peter Girguis describes a new seafloor experimental system called MIMOSA (Microbial Methane Observatory for Seafloor Analysis). This new system allowed the authors to measure microbial oil degradation rates and changes in microbial community structure directly at the seafloor. "Our goal was to track how quickly microbes consume oil on the seafllor. Instead of collecting sediment and bringing it back to the lab, which can introduce a lot of variables into the measurement, we wanted to do the experiment on the seafloor" says lead author Beth Orcutt. "We designed a new system to recreate a mini (contained!) oil spill on the seafloor and then tracked what happened in the sediment over the next five months. We collected samples continuously over that time period, both from the mini oil spill as well as a control experiment (no added oil)."

The major findings from this paper were that oil on the seafloor initially stimulates sulfate reduction and methanogenesis, two processes that different sets of microbes use in order to "breathe" while degrading the carbon in the oil (their food source). The sulfate reduction rates measured in this paper were some of the highest rates ever measured in the deep sea. However, these rates dropped off very quickly, meaning the microbes ran out of this fuel that they need to break down the oil. Over the course of the 5 month long experiment, only 0.6% of the added oil was degraded.

This new type of experiment demonstrated the ability of sediment microbial communities to respond to a large amount of oil, under conditions as close to their natural environment as possible. It is important for ECOGIG researchers to know how long the oil from the Deepwater Horizon will stay on the bottom, in order to determine the long term impact on the deep sea ecosystems in the Gulf.

back to top

back to top