March 17, 2016

Kelsey Rogers looks for evidence of oil and methane intrusion into Gulf of Mexico water and sediment, but finding these hydrocarbons is only the beginning of her work. Like a scientific crime scene investigator, Kelsey analyzes the chemical fingerprints of oil and gas and uses them to identify their source, such as from an oil spill or a natural seafloor seep.

Currently working towards her Ph.D. in Oceanography at Florida State University (FSU), Kelsey is a GoMRI Scholar with the ECOGIG 2 consortium. Kelsey talks of her journey from geology to oceanography and how every step along the way is important.

Her Path

“As a kid I had a huge rock collection—I loved to pick up anything shiny on the ground,” Kelsey recalled. She realized after her first undergraduate geology class at the University of North Carolina (UNC) Chapel Hill that she could make a career out of something that had always fascinated her. Working in the UNC isotope geochemistry lab, Kelsey wrote a research paper about using carbon isotope evidence from deer teeth to identify where the animals lived.

“Carbon isotopes are really awesome,” Kelsey said of her favorite research tool. “You can trace any number of things with them.”

(Click to enlarge) Kelsey Rogers onboard the R/V Endeavor, one of five field expeditions she participated in, collecting water and sediment samples in the Gulf of Mexico. (Photo provided by Ryan Sibert, Ph.D. Student, University of Georgia)

FSU oceanography professor Dr. Jeff Chanton frequently collaborated with researchers at UNC, where he previously studied and taught. Chanton was using isotope analyses to track the Deepwater Horizon oil spill and its potential impacts on the marine food web. Kelsey learned about Chanton’s oil spill research and saw a natural fit with her ecological research using carbon isotopes. She joined the first ECOGIG project as a master’s student in 2012 and also conducted research with the Deep-C consortium. Kelsey continues her graduate work with Chanton as a research team member with the second ECOGIG consortium.

Her Work

Kelsey identifies the carbon isotopes in Gulf particulate and sediment samples to track oil and methane through the marine ecosystem. She has joined five Gulf research sea expeditions since starting at FSU, collecting sediment at various depths and freezing them for lab processing. She also collected water column samples 20 liters at a time, then filtered and dried suspended particles for later lab isotope analysis.

Kelsey treats the samples with an acid wash to remove calcium carbonate from shells that could interfere with lab processing. Using a mass spectrometer at FSU, she calculates the stable carbon isotopes and then sends them to the University of Georgia to analyze their radiocarbon levels. These tests can take up to six weeks.

Click to enlarge) Kelsey Rogers processes samples onboard the vessel’s wet lab. (Photo provided by Kelsey Rogers, courtesy of Deep-C)

Click to enlarge) Kelsey Rogers processes samples onboard the vessel’s wet lab. (Photo provided by Kelsey Rogers, courtesy of Deep-C)

Certain key isotope numbers serve as chemical fingerprints, signaling that the samples contain oil and methane. Kelsey studies the stable and radiocarbon levels to determine how much oil and/or methane is present, how old it is, and where it originated. Natural seeps in the gulf are like hydrocarbon springs, releasing oil and methane to the Gulf’s water column. Kelsey can trace these hydrocarbons’ path through the water column using the carbon isotopes. She has found hydrocarbons consistent with a Deepwater Horizon point source and from GC 600, the largest natural seep in the Gulf.

Her Learning

Kelsey states emphatically that working on GoMRI projects has honed her skills while deepening her love for science. She credits the Compass science communication workshops with teaching her how to more clearly share her findings with different audiences.

(Click to enlarge) Kelsey Rogers worked alongside marine technician Jason Agnich to collect water and sediment samples from the Gulf of Mexico. (Photo provided by Professor Joseph Montoya, Georgia Institute of Technology)

The camaraderie among ECOGIG members has helped Kelsey develop professional friendships that will support her throughout her career. “I’ve met so many great people on these research cruises,” she said. “Everyone is so gung-ho about working together and helping one another. It’s a wonderful community.”

Kelsey’s advisor, Jeff Chanton, has taught her to go where her interests take her and not feel limited by her chosen field. Involved in many diverse projects himself, Chanton has shown Kelsey that oceanography skills are transferable to other subjects that strike her interest.

“With Jeff as my advisor, I don’t feel like I’m pigeonholed,” she explained. “He’s taught me you don’t have to do just one thing for your entire career—you can be creative.”

Her Future

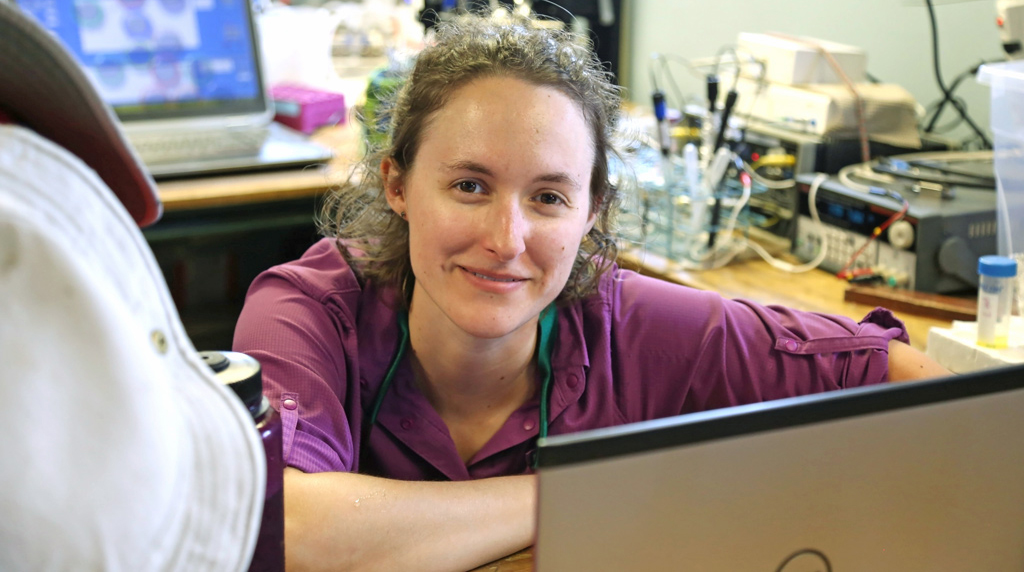

(Click to enlarge) Kelsey Rogers spent many hours processing samples in R/V Endeavor’s main lab. (Photo provided by Professor Joseph Montoya, Georgia Institute of Technology)

Kelsey expects to finish her Ph.D. in late 2017 or early 2018. Feeling drawn to an industry or government position, she wants to provide the most help in a future event, though she clarifies that might not be mitigation. “I don’t really want to do cleanup,” she said. “I want to get ahead of the problem.” She suggests finding ways to make exploration safer or helping to craft government environmental policies as possibilities.

Wherever she winds up, Kelsey believes all the steps along her journey are necessary and meaningful: “I started out as a beaker cleaner in the lab. But those beakers need to be absolutely sterile for the experiments to be valid. All the jobs in science are important.”

Praise for Kelsey

Chanton said Kelsey has boundless energy and is undaunted by difficult tasks. Her great attitude has led to a leadership role in the Thalassic society, FSU’s graduate school organization. A Thalassic project manager, she sits on the executive committee and assists the president and vice president in organizing and running different functions throughout the year.

(Click to enlarge) Researchers use a multi-corer to collect sediment samples in the Gulf of Mexico. (Photo provided by Kelsey Rogers)

“Kelsey has a can-do approach that is contagious,” Chanton said. “On the ECOGIG cruises, she never rests. When her own work is completed, she surveys the deck to see who needs a hand with theirs.”

Chanton said that in addition to field missions, Kelsey also shines at outreach events where she is engaging and patient when explaining her work. He said she can make complex topics as simple as they need to be depending on the audience, and her natural confidence puts people at ease.

The GoMRI community embraces bright and dedicated students like Kelsey Rogers and their important contributions. The GoMRI Scholars Program recognizes graduate students whose work focuses on GoMRI-funded projects and builds community for the next generation of ocean science professionals.

************

This article was written by Maggie Dannreuther at The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI). The original article can be found here.

This research was made possible in part by a grant from The Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative (GoMRI). The GoMRI is a 10-year independent research program established to study the effect, and the potential associated impact, of hydrocarbon releases on the environment and public health, as well as to develop improved spill mitigation, oil detection, characterization and remediation technologies. An independent and academic 20-member Research Board makes the funding and research direction decisions to ensure the intellectual quality, effectiveness and academic independence of the GoMRI research. All research data, findings and publications will be made publicly available. The program was established through a $500 million financial commitment from BP. For more information, visit http://gulfresearchinitiative.org/.

back to top

back to top