April 20, 2020

A dedication and perspective piece from ECOGIG Director Dr. Mandy Joye is available in its own post here. Below are perspectives from researchers who were there at the beginning - and end - of the largest oil spill in history.

Perspectives from Dr. Joe Montoya – ECOGIG Associate Director and Professor at Georgia Institute of Technology

Project Director Dr. Mandy Joye and Associate Director Dr. Joe Montoya.

What were you doing when you found out about the spill, and what were your initial thoughts?

The first news reports I heard were a bit vague, so it took a bit of time to really appreciate what was going on. My initial thoughts were that it was just another incident, and I certainly didn’t have a sense of the magnitude of the spill. My group was getting ready to leave for a research cruise in the tropical Atlantic, so we weren’t at all focused on the Gulf scientifically at that moment.

What have you learned about the Gulf in the 10 years since the spill?

We’ve learned a great deal about the ways that carbon from oil and gas (petrocarbon) moves through the Gulf ecosystem. The speed of the initial movement of petrocarbon through the planktonic ecosystem was impressive, and our continuing work has really opened our eyes to the persistence of that carbon in the particles and zooplankton. We’ve also found interesting links between carbon and nitrogen cycling in the Gulf which we don’t yet fully understand, but it’s clear that the two elemental cycles were both affected by the spill.

What do you wish you’d known about the Gulf pre-spill?

I wish we’d known more about some of the seep fields we began to explore and study a few years ago. These provide a range of depths and seepage conditions that have really expanded our opportunities to study the behavior of ecosystems exposed to petrocarbon inputs.

How do you think the Gulf is doing 10 years later?

Although many of the obvious impacts of the spill like large surface oil slicks and oiled beaches have passed, I think it’s still too early to say what the lasting impact of the spill will be on the Gulf. We have clear evidence for persistent biogeochemical impacts of the spill and have developed an appreciation for the seasonal and interannual variability of Gulf ecosystems through our extensive series of cruises and time-series measurements.

How has being a part of GoMRI helped connect you to the larger Gulf research community?

The annual GoMRI meetings have clearly provided an important venue for interacting with other Gulf researchers. The entire research community has benefitted from GoMRI’s efforts, which have made it possible to carry out a great deal of excellent, collaborative science.

Perspectives from Dr. Luke McKay – Assistant Research Professor at Montana State University

Dr. McKay inspects a gravity core. Photo courtesy of Louis Garcia, LSU

What were you doing when you found out about the spill, and what were your initial thoughts?

I was on a cross-country road trip, hauling scientific gear from San Diego to Chapel Hill, NC. A few months prior, we completed a research cruise in the Gulf of California and we needed to retrieve our equipment from R/V Atlantis docked at SCRIPPS Institute of Oceanography. I believe we were passing through Alabama (my home state) when my PhD advisor from UNC-Chapel Hill, Prof. Andreas Teske, called me and asked if I would hop on another ship to take the first microbiology samples of the DWH oil spill.

How did you get involved in researching the spill?

I was a graduate student at UNC-Chapel Hill with marine microbiology sampling experience and always eager for the next adventure. Once the call came for me to fly to New Orleans and board the R/V Pelican, I stopped by Dr. Joye's lab UGA and she outfitted me with rapid response sampling supplies, a couple of coolers, and a camera. I still remember Mandy telling me to "take LOTS of pictures".

What are you doing now, and how did the spill shape your career path?

I am an Assistant Research Professor at Montana State University where I investigate microbial sulfur and methane metabolisms in high-temperature environments, mostly in Yellowstone National Park. Microorganisms degrade hydrocarbons like methane and higher alkanes in the environment, whether they are naturally occurring or result from anthropogenic contamination like the oil spill. My research into the oil spill resulted in five co-authored publications and involved laboratory techniques that are important to my work today, such as fluorescence in-situ hybridization (FISH) to identify microbial species of interest under the microscope.

How do you think the Gulf is doing, 10 years later?

This is a difficult question to answer. There is so much we don't know about the status-quo of ocean microbiomes (surface, subsurface, sediments) so it is hard to say the extent to which these systems were impacted compared to what they were before. Not to mention, recent reports suggest that the extent of the oil spill was greater than our estimates from satellite data at the time (Berenshtein et al., 2020). What we do know is that massive amounts of oil leaking from the wellhead diversified into different oil subtypes by physical, chemical, and biological processes and distributed into different locations in the Gulf. Diverse microbial communities were observed degrading diverse oil types in diverse environments, and there are likely certain ecosystems that are still impacted today (perhaps deep ocean sediments where oxygen is limited). If I learned anything from this experience it is that understanding marine microbiology is crucial to our broader understanding of ecology and environmental biology. These concepts are all the more imperative for us to comprehend when faced with environmental disasters like the DWH oil spill.

Perspectives from Dr. Erik Cordes – Professor at Temple University

Dr. Cordes in a ROV control van at sea.

What have you learned about the Gulf in the 10 years since the spill?

In the process of determining the impacts of the spill, we discovered a number of amazing new deep-sea coral sites. These have taught us a lot about the distribution of corals and their habitat requirements in the deep ocean.

How has working on the spill shaped your research?

The spill completely changed what I work on in my career. A large part of the work in the lab focused on the impacts and on the response of the corals to oil and dispersant exposure. It also led me down a path investigating offshore drilling impacts and regulations in a broader sense. I started the Oil & Gas working group of the Deep Ocean Stewardship Initiative (DOSI), which now has members all over the world.

What do you wish you'd known about the Gulf pre-spill?

I wish that we had more basic knowledge of the deep-sea corals in the vicinity of the spill. We had no existing research sites nearby when the spill happened. It is amazing how little we know to this day.

How do you think the Gulf is doing 10 years later?

There have been some signs of recovery, but everything moves slowly in the deep sea. It will be another decade before we know how it is going to turn out.

How has being a part of GoMRI helped connect you to the larger Gulf research community?

GoMRI has been a huge boon to Gulf research and our basic understanding of how systems react to oil spills. It will have an enduring legacy in the volumes of publications that have come out of ECOGIG and the other consortia.

Perspectives from Dr. Melitza Crespo-Medina – Researcher at Inter American University of Puerto Rico; CECIA

Dr. Crespo-Medina at sea, near an offshore oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico.

What were you doing when you found out about the spill, and what were your initial thoughts?

At the time, I was working as Post Doc in Dr. Mandy Joye's lab. My research at the time was focused on methane dynamics in brine lakes from the Gulf of Mexico, but I was working with samples previously collected by others in the lab, so I had never been in the Gulf before. I think I had a mix of feelings. I felt sadness and anger, but at the same time some sort of feeling of excitement to be able to be part of the small group of scientists that were out there to do research.

What are you doing now, and how did the spill shape your career path?

I am currently a Researcher at the Center for Environmental Education, Conservation and Research (CECIA) from the Inter American University of Puerto Rico. I am involved in different projects that range from microbiology in potable water to the ecology of mangrove forests in the Island. It has been very interesting to be able to apply all my environmental microbiology expertise to different scenarios.

I do a lot of work with remote communities in the Island, and although I can drive to my field sites now, the sites are not that easily accessible, and are far from our laboratory so you need to be extra prepared for every field trip. I think that doing research during the spill prepared me for any kind of field work. We used to pack half of the lab into a moving truck, we always had extra supplies just in case we encountered a different sampling opportunity - I do the same now. I am always prepared to collect whatever extra samples I can find and I’m always taking notes and documenting what happen around me during field trips and lab work. That is something I learned while doing research during the spill.

How do you think the Gulf is doing, 10 years later?

l haven’t done Gulf related research in years, but I sure hope that things have improved. I think that it is a very dynamic environment and that the ecosystems slowly have adapted to the consequences that this tragic event brought with it. What I witnessed during the time was very impressive and it was hard to imagine what the consequences would be, but I think that thanks to all the follow-up research and to the long term research that has been done since the spill, we now understand more about the resilience and adaptability of the environment.

Perspectives from Dr. Annalisa Bracco – Professor at Georgia Institute of Technology

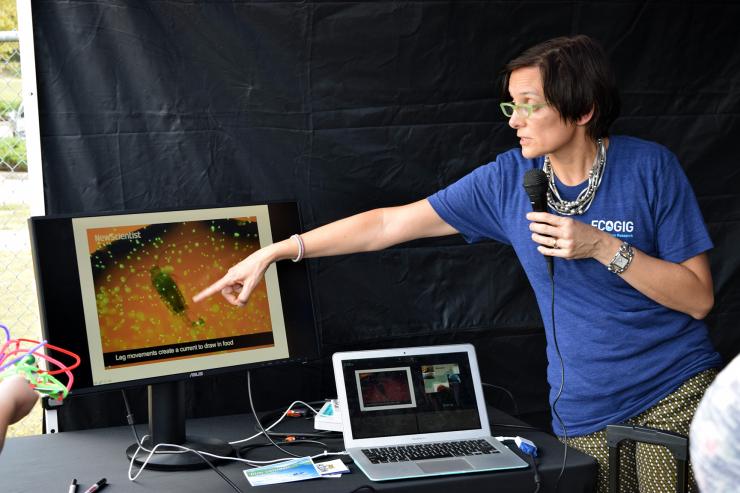

Dr. Bracco talking with students at a middle school outreach event.

What have you learned about the Gulf in the 10 years since the spill?

That we still do not understand and model well how tracers (active and passive) move in the Ocean. We have learned a lot but more needs to be understood. We also increased appreciation for the linkages between physical, chemical and biological processes. None can be understood without the others.

How has working on the spill shaped your research?

I never imagined I would have modeled coral connectivity, or carbon drawdown in the Gulf of Mexico. But all the data collected by ECOGIG really allowed my group to explore new topics, gaining a better understanding on processes and mechanisms that impact the whole ocean, not just the Gulf of Mexico.

What do you wish you'd known about the Gulf pre-spill?

From a physical standpoint, it would have been important to have better quantitative information of how the transport and mixing of material occur at depth, along the continental slope of the Gulf of Mexico.

How do you think the Gulf is doing 10 years later?

Considering the huge amount of oil, methane and dispersants released in 2010, better that I was expecting. But I doubt it could sustain another spill of comparable size. The ecosystem is recovering, but it needs time, especially at depth.

How has being a part of GoMRI helped connect you to the larger Gulf research community?

It has helped me keeping track of all the incredible science that was moving forward, and has helped me broaden my research horizons.

Perspectives from Dr. Kate Segarra – Coastal Science Lead for the New Orleans Regional Office at the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM)

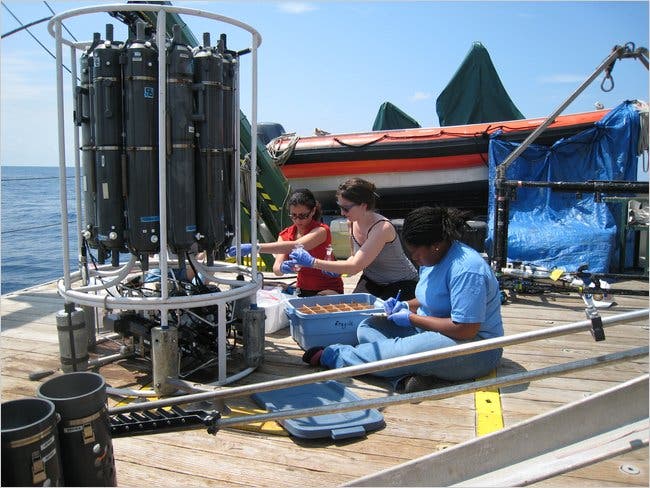

Dr. Segarra on board the RV Walton-Smith, taking samples of the Gulf, right after the Deepwater Horizon accident. Photo courtesy of the New York Times.

Note: The opinions expressed in this article are Dr. Segarra's own and do not reflect the views of the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, the U.S. Department of the Interior, or the United States government.

What were you doing when you found out about the spill, and what were your initial thoughts?

When I first learned of the spill I was listening to the news while working in the lab. I am from the Gulf Coast and I was immediately concerned for the region and its wildlife. The Coast was still reeling from Hurricane Katrina and its aftermath. The spill felt like a real kick to the stomach for a region trying to recover.

How did you get involved in researching the spill?

I was in the right place at the right time. I was a PhD researcher in Dr. Mandy Joye's laboratory at UGA. I was wrapping up my dissertation and wasn't planning on any more field work. But when I heard about the response cruise Mandy was mobilizing, I quickly volunteered to join the science party. We departed on the R/V Walton Smith about a month after the spill started. The well was still spewing oil while we were out there and would continue to do so for several more weeks.

What are you doing now, and how did the spill shape your career path?

I am currently the Coastal Science Lead for the New Orleans Regional Office in the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM). BOEM is one of the Bureaus in the Department of the Interior that formed from the splintering of the Marine Minerals Service (MMS) after the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill. Before the spill, I knew I wanted to work in marine science and policy. My involvement with the spill showed me how the importance of strong environmental policy and practice and how critical good science is to inform policy. I've been working at that intersection ever since graduating from UGA.

How do you think the Gulf is doing, 10 years later?

This is a great question but also a very difficult one to answer. Of course, it depends on where you look and how you look at it. The Gulf of Mexico is such an industrialized ecosystem with many ongoing stressors that are unrelated to the oil spill, such as overfishing, shipping, pollution, eutrophication, routine oil and gas activities, wetland loss, and climate change. It's difficult to tease apart the comprehensive impacts of any one issue. On a positive note, the wake of the oil spill brought renewed attention and research funding to the region. The RESTORE Act and BP settlement created long-term research networks and have funded several successful restoration efforts. The Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill was such a devastating yet pivotal moment for Gulf research and I feel lucky to have been a small part of it.

Perspectives from Dr. Amanda Demopoulos – Research Benthic Ecologist at the U.S. Geological Survey

Dr. Demopoulos with a sediment core. Photo by Andrea Toran, USGS.

What were you doing when you found out about the spill, and what were your initial thoughts?

I have conducted benthic ecology research at the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) in Gainesville, Florida since 2007. Looking back at that time, it was very chaotic for me in many ways. I was in the midst of planning a one-month field sampling effort in St. John, U.S. Virgin Islands (USVI), but I was also keeping my ear to the news at all times. Initially, after I heard about the explosion, I was concerned about the people who were on board the rig, their safety, and concerned for their families. It is a very difficult job to work offshore and can be very risky.

As the spill continued over days and weeks, I became concerned about the oil spill containment, how widespread the spill might become, and potential environmental impacts. My research focuses on benthic communities found in both coastal and deep-sea environments and I was increasingly concerned that both areas may experience impacts from the spill. As I was reading the news, it struck me as surprising that some of the articles indicated that oil being dispersed at depth would not have an impact because nothing much lives in the deep sea. This seemed unreal to me, since countless studies had been published about deep-sea organisms that thrive in the Gulf, including sensitive coral species. The deep Gulf is hardly a desert.

How did you get involved in researching the spill?

Since I joined USGS in 2007, my research team had been collaborating with government and academic scientists and managers on investigating deep-sea coral habitats in the Gulf of Mexico (GOM). This work spanned multiple years and was sponsored by the National Ocean Partnership Program (NOPP) and was joint funded by Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM-formerly Minerals Management Service), USGS, and National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration – Office of Ocean Exploration and Research (NOAA-OER). Because of my experience as a benthic ecologist and my work in the GOM, I was invited to participate in early discussions and lead the development of a plan to conduct impact assessments for the Natural Resource Damage Assessment (NRDA).

In addition, I was invited to help assess the impact of the spill to coastal beach sediment communities, including areas that serve as food forage habitats for birds. This work involved guiding pre- and post-impact beach collections along barrier islands, mainland beaches, and wetlands along all the Gulf coast states. Pre- and post-impact invertebrate collections were compared to identify short-term changes in these communities to enable insight into oil-disturbance impacts on the benthic community structure and function and aid with subsequent long-term monitoring.

Within weeks of the spill occurring, I became involved in daily conference calls. Given I was in the midst of fieldwork in the USVI, I was juggling daily sampling scuba dives with guiding upcoming impact assessments via these calls. Some of the calls I took between dives while on the dive boat. I remember vividly that on one call I couldn’t mute my phone so I was the irritating person who had wind rustling in the background. These daily calls led to identifying who could help with the assessment, followed by gathering existing information, including assembling GIS data to map known and potential locations of mesophotic and deep-sea coral habitats relative to the spill. Ultimately, I sailed every month for the remainder of the year to conduct oil-spill impact assessment research.

Following marathon phone call sessions with colleagues from academia and government, we developed our sampling plan for a remotely operated vehicle (ROV) offshore research expedition in July 2010. I served as co-chief on the expedition with Charles Fisher (Pennsylvania State University) for the first leg and Kenneth Sulak (USGS) on the second leg, to assess possible impact to mesophotic and deep-sea coral habitats. Then, in November 2010, while sailing on the NOAA Ship Ronald H. Brown and using Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute’s ROV Jason, we discovered impacted coral colonies and impacted environments. We collected coral specimens, sediments, and water samples for hydrocarbon and community analysis. In addition to leading the impact assessment to the sediment communities, I was in charge of ensuring specimens were transferred to appropriate labs and maintaining chain of custody records which was a brand-new responsibility for me, requiring very detail-oriented notes and procedures.

For the first year after the spill, I continued advising NRDA on the DWH impacts to deep-sea communities and working with colleagues funded through the GOM Research Initiative-Ecosystem Impacts of Oil and Gas in the Gulf program. This allowed me to collect and examine samples to assess changes in the benthic communities over time since the spill, leading to a unique long-term dataset for deep-sea environments.

What are you doing now, and how did the spill shape your career path?

My research continues to examine benthic communities in complex environments and in different ocean basins, including the GOM as well as the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. I have learned a great deal since the spill that has helped me with my research and collaborations. The oil spill assessment provided me with access, not only to the remote environments that I study, but also to a rich network of collaborators who are great to work with, and I continue to work with many of these scientists today. While the spill was devastating, it inspired a tremendous amount of innovative technology development and high-quality research that will provide avenues for research to come. I feel fortunate to have been part of the team that helped assess the impact of the spill to the deep-sea environments, and I continue to help guide future restoration and monitoring plans. The knowledge and experience that I gained being part of that team has informed how I approach all of my research programs, collaborations, and partnerships since then.

How do you think the Gulf is doing, 10 years later?

In general, I’m impressed by how resilient the Gulf is in so many ways. I try to attend the Gulf of Mexico Oil Spill Ecosystem Science conferences every year and the wealth of research and new information that has been produced over the past 10 years is incredible. We know much more about the Gulf of Mexico now than we ever did before. While we knew where some of the deep-sea corals were located before the spill, the coral habitats that were impacted weren’t discovered until 4 months after the spill occurred. It took the spill, subsequent NRDA assessments, collaborative GOMRI-funded research programs, and improving public-private partnerships to better understand many aspects of the deep GOM, what makes it tick, where we find deep-sea coral habitats, and their overall resiliency.

My research team has been tracking changes in benthic communities annually since 2010, with our most recent collections from 2017 (Bourque and Demopoulos 2019). We’ve found that the communities at the impacted sites continue to change year to year and they do not resemble those found at non-impacted sites. Because change happens very slowly in the deep sea, it may take some time before they return to pre-spill conditions. However, we are interested in revisiting those sites, since it has been 3 years since our last collections and assessment. Based on work conducted on sediment communities in the GOM by Montagna and colleagues (2016), it could take decades or longer for these systems to return to pre-spill conditions. Continued monitoring of these areas will help us understand the trajectories and timescales for recovery in these remote environments.

Perspectives from Dr. Kai Ziervogel – Professor at the University of New Hampshire

Dr. Ziervogel taking water samples at sea.

What have you learned about the Gulf in the 10 years since the spill?

Everything I now know about the system was new to me, as I was rather ignorant towards the Gulf prior to the spill.

How has working on the spill shaped your research?

I started translating my knowledge from the spill in the Gulf to other ecosystems that are potentially threatened by an oil spill, such as the Gulf of Alaska.

What do you wish you'd known about the Gulf pre-spill?

I actually did not know much about the Gulf before the spill other than what was in the news (eutrophication, dead zones etc.); given this ignorance, I am still very excited and enthusiastic about the Gulf as I am still learning a great deal about how these ecosystems work.

How do you think the Gulf is doing 10 years later?

Some areas of the ecosystems have recovered, others are still affected by the influence of the spill.

How has being a part of GoMRI helped connect you to the larger Gulf research community?

It has helped me so much, collaborations within GoMRI grew stronger over the years and have helped me build up my career in oceanography.

Perspectives from Dr. Uta Passow – Canada Research Chair at Memorial University

Dr. Passow working with samples in the lab.

What have you learned about the Gulf in the 10 years since the spill?

It is a beautiful, vibrant, very diverse and amazing ecosystem, full of biological treasures and surprises. It should be considered a national treasure and protected to a much, much larger extent! Future generations will regret it deeply, and blame us if we do not do this!

How has working on the spill shaped your research?

It was my introduction of oil spill research. I had worked on marine snow for decades, but never in the context of oil spills. Working on the Deepwater Horizon spill added a more applied component to my research. No one wants spills. But when they happen it is useful to have the knowledge and a plan to minimize long-lasting damage.

What do you wish you’d known about the Gulf pre-spill?

We would have needed better and more background data on almost every aspect of the Gulf of Mexico ecosystem. I specifically would have needed data on the seasonality of the coastal and open ocean planktonic ecosystem, including nutrient inputs, plankton successions, seasonal changes in export flux and benthic-pelagic coupling.

How do you think the Gulf is doing 10 years later?

Given the amount of oil spilled, the Gulf of Mexico is doing amazingly well. But overall the Gulf of Mexico is threatened, not only by oil spills, but by many other human impacts, such as pollution, warming, ocean acidification, overfishing. It is time to make a comprehensive plan that helps protect the whole region.

How has being a part of GoMRI helped connect you to the larger Gulf research community?

Oceanography is very collaborative; it is a team sport. The work of the last 10 years has connected me to many colleagues working on different aspects and in different regions of the Gulf of Mexico.

.jpeg)

back to top

back to top