April 20, 2020

A dedication from ECOGIG Director Dr. Mandy Joye:

I want to start by sending my condolences to the families of the eleven brave men who died on the Deepwater Horizon - Jason Anderson, Aaron Dale Burkeen, Donald Clark, Stephen Ray Curtis, Gordon Jones, Roy Wyatt Kemp, Karl Kleppinger, Jr., Keith Blair Manuel, Dewey Revette, Shane Roshto and Adam Weise. I cannot imagine your pain today and my heart goes out to all of you.

I also want to recognize two important people who were instrumental in our Deepwater Horizon research that we lost since then – Ray Highsmith and Vladimir Samarkin. I want to thank Ray and Vladimir for all of their efforts and for their commitment to our work in the Gulf. Ray was the director of the National Institute for Undersea Science and Technology (NIUST) at the University of Mississippi. He was instrumental in enabling our Deepwater Horizon response efforts. Ray was also the founding director of the Ecosystem Impacts of Oil and Gas inputs to the Gulf (ECOGIG) consortium. Our collaborative team would not have been able to accomplish what it did without Ray’s support. We lost Ray in 2013. Vladimir was a research scientist in my group. He was a big part of our Gulf of Mexico work in the eight years prior to the Deepwater Horizon disaster. We lost Vladimir in 2017. Vladimir was a science ninja – his ability to design an experimental approach to tackle a tough question or to MacGuyer a solution when he lacked many of the items most folks would consider necessary was unmatched. I miss our science talks and I miss his humor: Vladimir was hilarious. His Russian jokes often left me laughing so hard I had to gasp for air. Vladimir kept everyone smiling and made working at sea or in the field a joy. The two of us spent days on end in the 4ºC cold room on R/V Atlantis and R/V Seward Johnson and in the lab at SNARL in the Sierras. The time in the cold room passed fast and difficult tasks were accomplished with ease when we worked together. Vladimir was one of the brightest people and deepest thinkers I’ve known. Our discussions often led me to ideas that I doubt I would have reached on my own. I treasured our intellectual synergy and our friendship. Vladimir, you were one of a kind; I miss you.

Perspectives from Dr. Mandy Joye - ECOGIG Project Director and Regents' Professor at the University of Georgia

What were you doing when you found out about the spill, and what were your initial thoughts?

In the early morning of April 21, 2010, I received email from a colleague who was out on the R/V Pelican at MC118, the site of a long term Gas Hydrate Observatory program. The MC118 Observatory was an interdisciplinary program and the work included a number of different teams and broad portfolio of research goals. My role in the Observatory involved studying the microbiology and biogeochemistry of gas hydrates, oily sediments, and the water column.

On that fateful day in April 2010, the hydrate observatory team was on board the R/V Pelican working at MC118 to collect routine samples. We had sampled recently (on March 20, 2010) so had valuable pre-Deepwater Horizon water column samples in hand for comparison. After reading the email, I knew something terrible had happened – I received reports of irregular ship traffic during the night and of billowing plumes of smoke at daybreak. I started digging around to see what I could find out. After a lot of web searching and phone calls, I discovered there had been a blowout. It was surreal and I had a horrible feeling about the developing situation – a sense that the challenge would last for a long time. The knot that developed in my stomach that day did not go away for almost two years.

I called Ray Highsmith that day (21st) and the next (22nd) and we talked about re-mobilizing the Pelican as fast as possible; the team had been told to leave the scene and had to return to port. I felt it was critical to start sampling as soon as possible. And I wanted to do something to help. Ray arranged for the shiptime on the R/V Pelican and Arne Diercks and Vernon Asper agreed to lead the expedition. I wrote a RAPID proposal to the NSF in the next days, proposing to look for for deepwater plumes and sedimented oil and to understand how those two things altered pelagic and benthic metabolism. I knew that our work could make a difference.

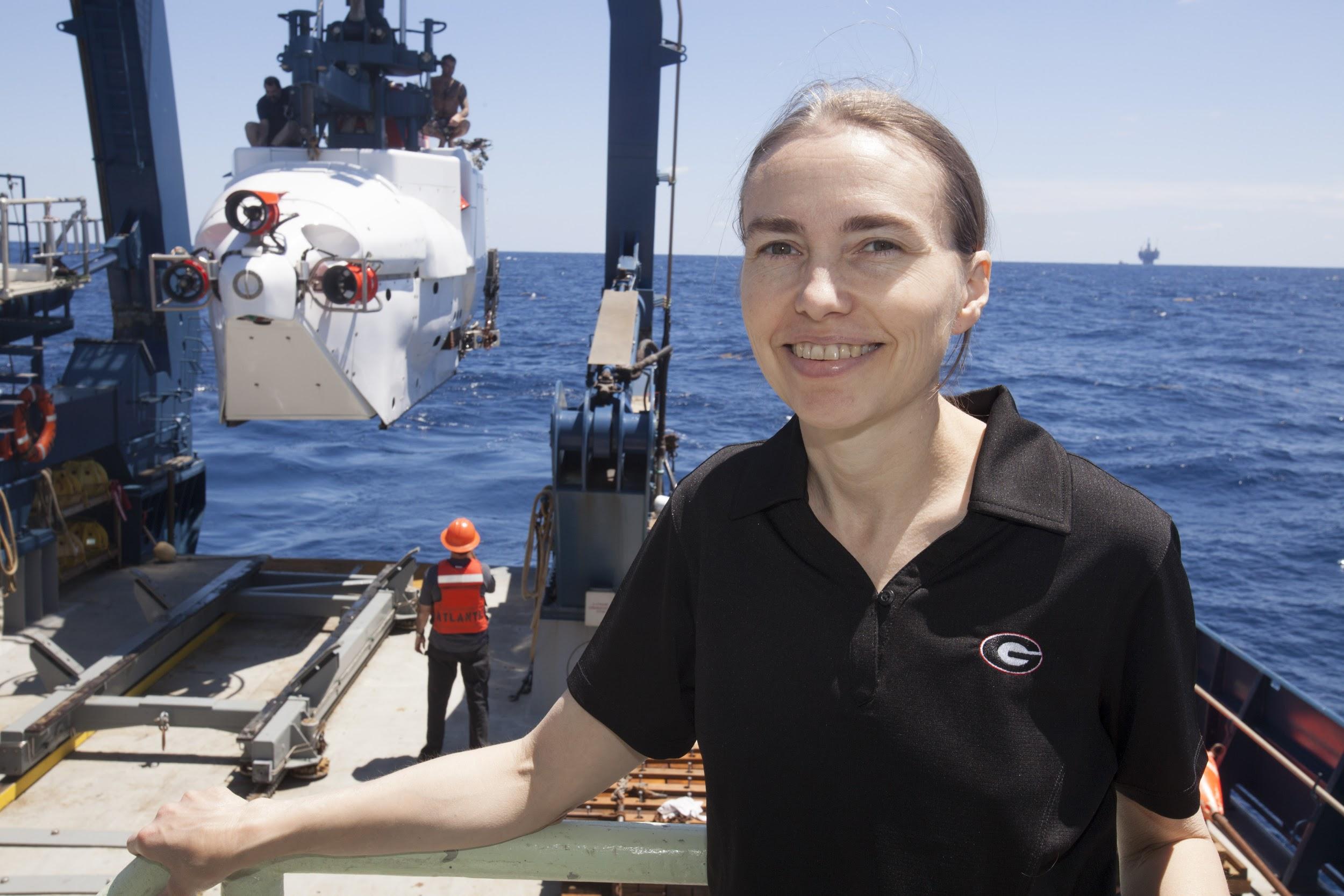

Dr. Mandy Joye and the research submarine ALVIN in the Gulf of Mexico. Photo courtesy of UGA.

What have you learned about the Gulf in the 10 years since the spill?

In addition to scientific discoveries, being involved in the Deepwater Horizon response taught me a lot about doing successful science – particularly team science.

- System Knowledge: I completed my first expedition to the Gulf of Mexico in 1994, when I was a postdoc. I fell in love with the Gulf and focused much of my ensuing work on exploring deep sea extreme environments there, working to build a base of knowledge that would advance understanding of the regulation and dynamic of these amazing habitats. When the blowout happened, my previous research experiences provided the expertise necessary to make a significant contribution to the response effort.

- Intuition: Experience and expertise lead to intuition. When I was writing my NSF RAPID proposal, I proposed studying the pelagic and benthic impacts of the blowout. I chose those topics because I had read about plumes but for the benthic impacts, I don’t know why but I had a feeling that sedimentation would be important. That idea arose from intuition – I’m not sure why I felt there would be a benthic impact, but I did. As it turned out, sedimentation was a significant fate of the discharged oil.

- Team Science: Before the Deepwater Horizon, I had been involved in a number of large collaborative projects – the Chemosynthetic Ecosystems (CHEMO) projects and the MC118 Observatory, for example – but the Deepwater Horizon response was something else entirely. Our initial response effort included geologists, chemists, and microbiologists. We quickly invited deep sea biologists, physical oceanographers, biological oceanographers, and experts in genomics and remote sensing to join our team. Then, we brought in colleagues with expertise in time-series measurements and in-situ instrumentation. The end result was a large, transdisciplinary team that had the necessary expertise to assess impacts of the spill from the sea surface to the seafloor, on time scales of hours to decades. What made our team successful – trust, good communication, and a shared passion for our work. Everyone understood their role and worked together to foster the success of the program.

- Scientific Discovery: In terms of the Deepwater Horizon, our team discovered the deepwater plumes and we were the first to recognize the importance of oil sedimentation. We applied genomic and bioinformatics tools in new ways to discover new microorganisms involved in oil and gas degradation and to track the microbial response to the skill. We helped document the role of the ‘rare biosphere’ in the system’s natural response to the spill. We documented the time scale of recovery of water column and benthic environments. We used naturally occurring isotopes of carbon and nitrogen to track where the oil and gas ended up and how it was cycled in the system. We built new technology to “take the pulse” of sediments and of the water overlying them. The knowledge we gleaned provides a solid foundation upon which to build new collaborative research systems that will continue to advance discoveries in the Gulf, and in the Ocean as a whole.

Dr. Mandy Joye and ECOGIG PI Dr. Erik Cordes, discussing an expedition. Photo courtesy of DEEPSEARCH expedition.

What do you wish you’d known about the Gulf pre-spill?

Like every student entering the field of Ocean Science, I took a physical oceanography course. I labored through it, finding many of the topics difficult. I learned more in physical oceanography than any other course (thank you Dr. John Bane, for being a great professor!). Prior to Deepwater, I knew that the Loop Current shaped circulation in the Gulf and I knew how the “Dead Zone” formed each year off the Texas-Louisiana Shelf. But, I did not factor physics or biological-physical coupling into the interpretation of my results. I did not appreciate the extent to which physics dictated the behavior of the deepwater plumes – how the complex topography of the seabed served to accelerate vertical mixing and how that erased the plume signature over time. I did not appreciate that the Gulf’s dynamic circulation would end up transporting oil and gas degrading bacteria far away from the incident area, essentially spreading excess biomass across a wide spread area far beyond what I would have predicted. I did not appreciate how different circulation is to the east vs. west of Mississippi Canyon – how the location of a blowout (Mississippi Canyon vs. Green Canyon, for example) would lead to a very different distribution of discharged oil. I did not realize how the timing of a spill – spring vs. winter – could lead to a different oil distribution, because of differences in physical circulation. I did not realize how much I enjoy thinking about the role of physics in regulating biological – and biogeochemical – dynamics in the system! I began collaborating with a lot of new people during Deepwater but my physical oceanography colleagues – especially Annalisa Bracco and Claire Paris – taught me so, so much. The way I think about the Gulf system is different now and I will be able to ask more relevant questions because of this change in viewpoint.

.jpg)

Dr. Mandy Joye on the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico, observing a brine pool and advising filming during the BBC series Blue Planet II

How do you think the Gulf is doing 10 years later?

The Gulf is resilient; there is no doubt about that. On the surface, the system appears the same, but some habitats remain damaged and have not recovered while in others, subtle changes could affect system function. In the water column, shifts in microbial taxa persisted for several years and carbon cycling was disrupted for >three years. How changes at the base of the foodweb propagate up and impact higher trophic levels is unclear. Decreases in fish stocks and in top consumers like Sperm whales have been reported. Are these two things connected? We don’t really know. But the declines in fish and cetaceans are very troubling. Additional research is needed to continue to track and understand these trends.

The damage to deep ocean habitats and the animals that live there, e.g. corals and macro- and meio- fauna, are on-going. These communities are likely to take several decades to fully recover. Continued work is needed to document the timing and trajectory of the benthic recovery.

One thing is clear – different compartments in the system responded on different time scales and that is an important result for future response and natural resource damage assessment efforts. The microbial response and the response at the base of the food web needs to be assessed frequently (weekly at a minimum) and over a broad spatial scale in the immediate aftermath of a perturbation and then monthly or bi-monthly for another couple of years. It’s better to have too much data than have your interpretations and understanding limited because too little data were collected. Similarly, we know that we have to track sedimentation of oil and benthic impacts more broadly. We need to do a better job assessing biological oxidation of oil and gas so that we can better constrain the fate of discharged hydrocarbons. Everything we learned can help advance our next response effort to make it more comprehensive and thorough.

How has being a part of GoMRI helped connect you to the larger Gulf research community?

GoMRI made it possible for us to forge a new transdisciplinary team. The group of scientists I worked with before Deepwater – Ian MacDonald, Jeff Chanton, Joe Montoya, Chuck Fisher, Erik Cordes, Amanda Demopoulos, Beth Orcutt, Laura Lapham, Pete Girguis, Christof Meile, Chris Martens, and Andreas Teske – joined forces with Annalisa Bracco, Uta Passow, Patricia Medeiros, Carol Arnosti, Kai Ziervogel, Vernon Asper, Arne Diercks, Ajit Subramaniam, Beizhan Yan, Andy Allen, and Andy Juhl to create a truly amazing research team. Together, we did incredible work and we made a number of key discoveries. Our efforts advanced the knowledge of Gulf ecology, biogeochemistry, and microbiology and oil spill science in general. Many aspects of our work - for example, the application of genomics to identify and track microbial sentinels of perturbation, the development of sensitive new rate assays to quantify oil and gas oxidation rates, and the implementation of isotopic tracers of oil fluxes and fate - will advance and improve future response efforts.

Beyond ECOGIG, GoMRI created a family of researchers, with a common purpose and a shared goal – shedding light on the dynamics of the Gulf system and enabling discoveries that revealed the mechanism of impacts and nature of recovery. GoMRI provided connections – Claire Paris, David Hollander, Tracey Sutton, Steve Murawski, Ed Buskey...to name a few - and science synergies that altered and advanced the scope and nature of Gulf science in profound ways. It is hard to believe that ten years have passed, that the GoMRI program will come to an end this June. Many seeds have been planted though, and collaborative efforts will continue to sprout in the decades to come.

Dr. Mandy Joye and artist collaborator Rebecca Rutstein in the submarine ALVIN

Dr. Mandy Joye and artist collaborator Rebecca Rutstein in the submarine ALVIN

back to top

back to top